Ear Equalization Techniques for Diving

As an otolaryngologist, I often see people who are having a hard time equalizing their ears on descent, especially during their initial open water training. They usually request to be checked for anatomical or other medical conditions that could be causing this problem. However, in almost every case, there is no such condition.

True Eustachian tube dysfunction in adults is rare, especially if the ears are well ventilated and working normally on the surface. And while a deviated nasal septum can cause problems equalizing the sinuses, it does not prevent ventilation of the ears. For most divers, the answer is to learn a technique that works for them, and then to practice it in the water. But whichever maneuver you use, never be reluctant to call off a dive if you can’t get it to work.

Your first attempt at ear clearing should happen before you even get in the water. If you can't equalize your ears on the boat or the shore, it's not going to get easier once you are at depth. You should never try to “push through” the pain. As the gradient between the middle ear and ambient pressure gets bigger, it gets harder and harder to equalize. This means that equalizing early and often is key. If for any reason you can’t equalize, ascend a bit and try again, or try a different technique. Also, some divers can eventually equalize, but it always takes them a long time. One of the most talented divers I know has this problem, and it's not an issue as long as they discuss a planned slow descent with their buddy ahead of time.

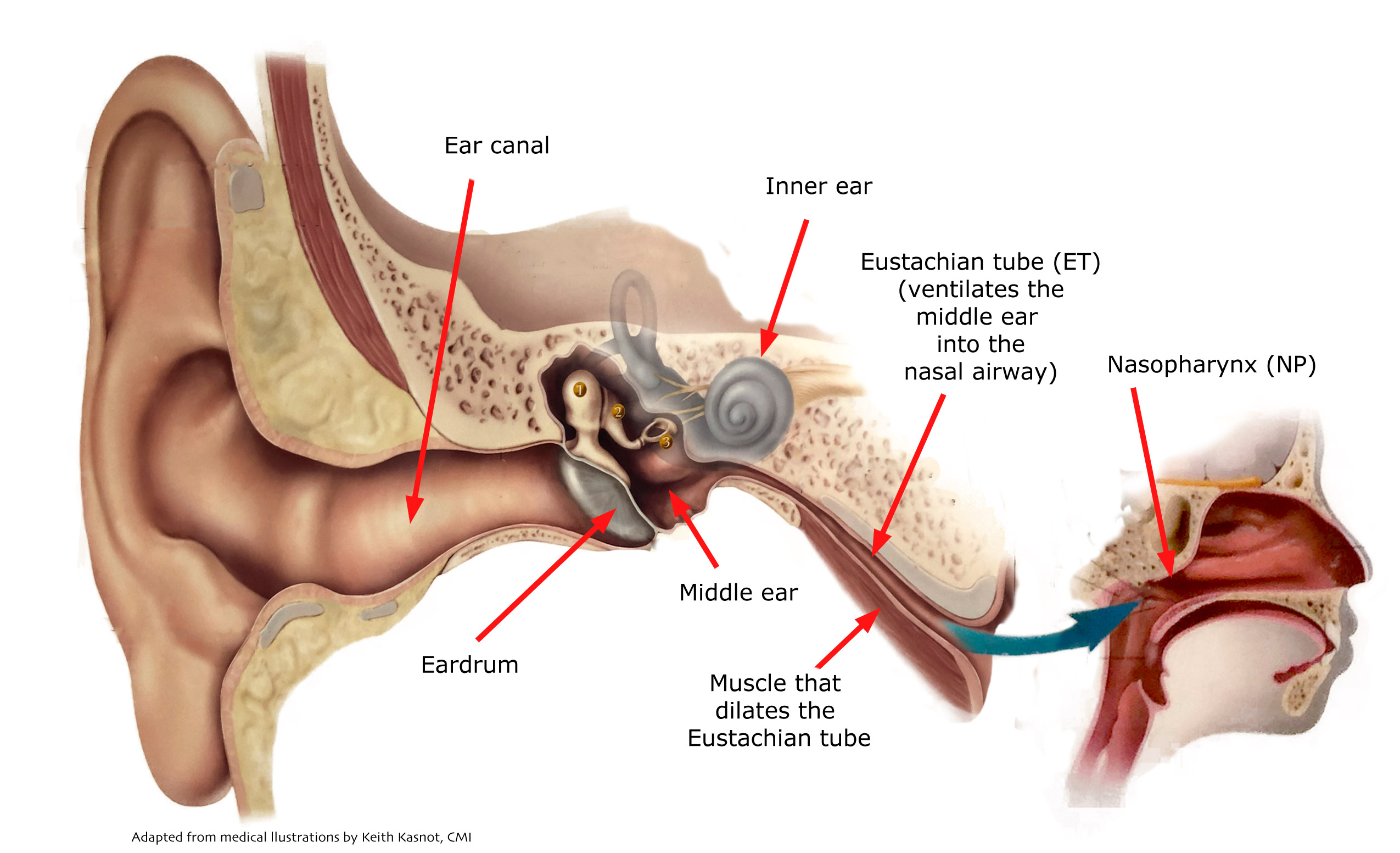

The most common technique for ear equalization is the Valsalva maneuver. The nose is pinched, followed by “blowing.” The diver has to force air into the back of the nose (the nasopharynx, or NP), to raise the pressure in the space where the Eustachian tube (the ET) connects to the airway. It's important to avoid puffing out your cheeks, as this is not effectively raising pressure in the NP. You can tell if you are doing it correctly because the sides of the tip of your nose (over the nostrils) will expand a bit as the pressure in the nasal airway increases. This maneuver lets the diver ventilate the middle ear space to keep up with rising ambient pressure on descent.

True Eustachian tube dysfunction in adults is rare, especially if the ears are well ventilated and working normally on the surface. And while a deviated nasal septum can cause problems equalizing the sinuses, it does not prevent ventilation of the ears. For most divers, the answer is to learn a technique that works for them, and then to practice it in the water. But whichever maneuver you use, never be reluctant to call off a dive if you can’t get it to work.

Your first attempt at ear clearing should happen before you even get in the water. If you can't equalize your ears on the boat or the shore, it's not going to get easier once you are at depth. You should never try to “push through” the pain. As the gradient between the middle ear and ambient pressure gets bigger, it gets harder and harder to equalize. This means that equalizing early and often is key. If for any reason you can’t equalize, ascend a bit and try again, or try a different technique. Also, some divers can eventually equalize, but it always takes them a long time. One of the most talented divers I know has this problem, and it's not an issue as long as they discuss a planned slow descent with their buddy ahead of time.

The most common technique for ear equalization is the Valsalva maneuver. The nose is pinched, followed by “blowing.” The diver has to force air into the back of the nose (the nasopharynx, or NP), to raise the pressure in the space where the Eustachian tube (the ET) connects to the airway. It's important to avoid puffing out your cheeks, as this is not effectively raising pressure in the NP. You can tell if you are doing it correctly because the sides of the tip of your nose (over the nostrils) will expand a bit as the pressure in the nasal airway increases. This maneuver lets the diver ventilate the middle ear space to keep up with rising ambient pressure on descent.

While the vast majority of divers use a Valsalva maneuver without difficulty, it is possible to cause injury in certain circumstances. Excessive pressure can cause pain, barotrauma or even eardrum perforation, especially if there is a preexisting weakness in the eardrum. Furthermore, if the ET is completely blocked, it is possible to cause an inner ear injury by transmitting increased pressure in the cerebrospinal fluid (around the brain) through a structure called the cochlear aqueduct.

There is also the possibility of eye injury with Valsalva in some patients with lens implants or retinal blood vessel disease. And there are even issues related to blood pressure and heart rate changes that can be problems for people with certain conditions, as this maneuver raises the pressure in the chest. This is all beyond the scope of this article, and most people at risk for these complications will know about them. In general, a gentle Valsalva in an otherwise healthy person is usually safe and effective. Just remember never to force it if it doesn’t work.

Another common method of equalization is the Toynbee maneuver. In this case, the nose is pinched, followed by swallowing. This is the “reverse” of the Valsalva maneuver, since the swallow causes reduced pressure in the NP, helping gas to flow out of the middle ear, and opening the ET to allow natural ventilation along whatever pressure gradient exists at that depth. I find that alternating Valsalva and Toynbee maneuvers can be effective in breaking a “vapor lock,” and I sometimes recommend this on the surface for divers with residual middle ear fluid or blood after barotrauma, if there is no other ear injury.

In addition to alternating Valsalva and Toynbee maneuvers, some divers find that they can do them simultaneously. This is the Lowry technique, where you pinch your nose, and pressurize the NP by blowing, and then swallow at the same time. This does require practice, but it is not very difficult.

The Frenzel maneuver increases pressure in the NP without raising pressure in the chest. To do it, you pinch the nose and try to make a “K” sound. This closes your vocal cords and raises the back of your tongue, which acts like a piston, compressing the space of the upper airway. In addition to avoiding any risk of cardiovascular problems, this technique is gentler than the Valsalva maneuver, and is unlikely to cause ear injury. Here is a video by a free diving instructor demonstrating this maneuver in some detail.

Pressurization maneuvers (i.e. Valsalva and Frenzel) can be enhanced further by moving the jaw forward and down at the same time, which helps open the ET to allow equalization. Tensing the muscles of the roof of the mouth (the soft palate) will help with this process. This is known as the Edmonds technique.

Finally, there is BTV. Developed by the French Navy, this stands for “Beance Tubaire Volontaire,” and is also known as VTO (“Voluntary Tube Opening”). This is a maneuver where you consciously activate the muscles that dilate the ET. It is very safe, and it is also hands free, so it can be especially helpful to free divers or underwater photographers. However, not everyone can get the hang of this. Imagine the activity in your throat that happens with a yawn - this is similar to the BTV action. There are a number of online resources that can guide you if you want to try this approach. A more complex variant of this is the Roydhouse maneuver, which adds the activation of the muscles moving the uvula as well as the jaw and tongue muscles.

But remember, no matter which method you use, the most important thing is this - if equalization is not possible, diving is not possible. And any diver can call off any dive at any time for any reason!

Valsalva Maneuver

Tonybee Maneuver

Lowry Maneuver

Freznel Maneuver

Edmonds Technique

BTV Technique